Nov 28: Arrival

This morning, we prepped for another flight with 6 am wake-up for a 9 am flight. Since we’d already checked our bags before our unfortunate boomerang yesterday, we could sleep in a bit. The plane was hot, stuffy, and uncomfortable again and the Italian Air Force was stricter about enforcing proper carry-on size. We squeezed back behind the cargo again, exhausted and grumpy from yesterday’s flight, and plopped down in our uncomfortably tight seats.

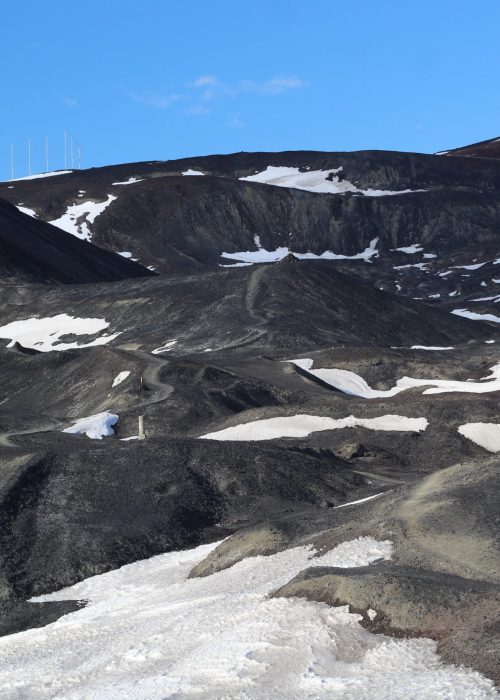

About 6 hours into the flight, we could finally see it – sea ice! There were enormous icebergs floating in the ocean surrounding the continent that the passengers were absolutely drooling over (myself included). Soon, we started to see vast expanses of icy mountains, deep crevasses, and glaciers flowing off of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. We were told to sit down and buckle up as the Italians landed the plane safely on the Ross Ice Shelf. We hopped out of the plane directly onto the ice shelf, stepping foot in the blinding white of Antarctica, many of us for the first time ever. We boarded an enormous bus called the CRESS and settled in for the hour-long shuttle to McMurdo Station.

When we arrived at McMurdo, we shuffled into the Crary library for a station briefing, followed by checking into our dorms, and grabbing a quick bite to eat from the galley. Dylen, Ilyse, Ellen, and I share a room in the main building 155, where the galley, a gym, offices, and other resources live. Forest and Elliot are next door to us while Zoe has been living in a nicer dorm meant for those who stay in McMurdo for longer than just a couple of weeks. The crew who had just flown in were pretty delirious but we picked up our luggage and got a tour of the station from Ellen, Forest, and Elliot who have been here before. Some highlights include the chapel, a couple of bars, the Skua (a free “thrift shop” to which people donate clothing, books, and other goods), the Crary science building, and views of the various hikes we can do around the station.

Many people have been at McMurdo for months already and the place operates like a small town – acronyms and nicknames for everything, camraderie amongst the residents, and a shared responsibility to keep the place sacred. As of 11/21/25, the population of McMurdo was 870 people. With many people arriving, staying only for a few days, then deploying for their various deep field work or moving onto the South Pole, this station sees a lot of movement. We’re incredibly lucky to be here.

Nov 29: Thanksgiving

This morning, we woke up bright (it’s always bright here) and early to get started with our day by completing a required sexual harassment training and setting up our lab. We’re a few days behind schedule due to the delays getting onto the continent. Almost all of our heavy, bulky, and delicate science cargo has already arrived and been plopped outside of Crary, ready for us three strong graduate students and one postdoc to haul inside…

We settled into our lab space today by trying to decipher what we’d packed in boxes months ago, and hauling some of the equipment into our small lab space allotment. Dylen and Ilyse are finishing up construction of strain gauges and parts for temperature measurements while Ellen and I are assembling our shiny new ice-penetrating radar.

Since our arrival date was delayed, our put-in date to the deep field is also delayed. We’ll have about two weeks in McMurdo before we can leave for Taylor Dome, and we have a long list of trainings to do in the meantime: field safety, GPS operation, high frequency radio, snowmobile, and the Deep Field Shakedown (DFS) to name a few. The DFS is a simulated field experience – a night of sleeping on the ice sheet to make sure we know what we’re in for. We’ll learn how to set up our tents and sleep kits, how to stay warm, and how to sleep during the 24-hour sunlight. More about these trainings later.

Another item on our to-do list is to request every unit of food we will need in the field for the ~6 weeks we’ll be out there. There’s a long list of food that is available for us to request, including snacks, frozen veggies, dehydrated meals (not a popular choice), tea and coffee, sauces, oils, and spices. The list includes the item, the amount of item in one unit, and whether the item can be frozen or not. It’s tough to guess what and how much food a group of 7-10 people with various dietary restrictions will eat after a 12-hour day of manual labor in the cold for 6 weeks, but it’s even tougher to decipher what a 32 oz bag of frozen peas means to us. How many gallons of olive oil will we need? How much rice should we cook for each meal? How can we request just enough food so that we don’t have too much and have to throw some away at the end of the season, but also so that we don’t starve? The food pull is quite tedious to put together.

Anyway, as you can see, we have quite a bit to do before we head out to Taylor Dome so we got straight to work today. But, today is Thanksgiving in McMurdo, so we celebrated with a fancy Thanksgiving dinner in the galley together and took the rest of the night to hike to the Robert Falcon Scott hut (built in 1904!) and play cribbage. Tomorrow, we’re back to the grind.

Nov 30: Field trip

Today we woke up and got straight to work – no rest when you leave for the field in two weeks! Since today is Sunday, it is McMurdo’s day off and most of the town amenities and offices we need to visit are closed. So, Ellen and I got to work on the food pull, compiling exact amounts down to the ounce of what we’ll need in the field. We’ve planned for:

- 6 x Burrito Bowl with Cheese Quesadilla x 2

- 9 x Curry

- 3 x Sushi Bowl

- 3 x Falafel and Hummus Bowls

- 3 x Breakfast for Dinner

- 3 x Chili

- 3 x Mac and Cheese

- 6 x Pad Thai

- 3 x Pasta Primavera

- 3 x Mashed Potato Bar

- 3 x Soup and Grilled Cheese

for a total of 45 meals over ~6 weeks (42 days). We are planning for a few extra meals just in case, despite expecting a ~4-day delay in our arrival to the field. Ellen and I worked hard to ensure that everyone is well fed with at least one hot meal per day, trying to fit (frozen, canned, or dehydrated) vegetables into every meal. It’s not the most appealing list of items to pick from and I’m sure we’re all going to feel incredibly happy to eat fresh fruits and veggies when we get off continent.

The meals at McMurdo are prepared by a lovely team of stewies who work to cook food for hundreds of people with largely frozen, dehydrated, canned, and sometimes expired food. Though there are lots of food and drink options every day in the galley, fresh fruits and veggies only arrive with certain shipments and they are always a popular choice due to their rarity.

After lunch, Dylen, Ilyse, Ellen and I did some shopping at the McMurdo store, which has gear that sells out faster than the fresh fruit and veggies in the galley. Sizes and styles are quite picked over and you are particularly advantaged if you wear a size small or women’s size… anything.

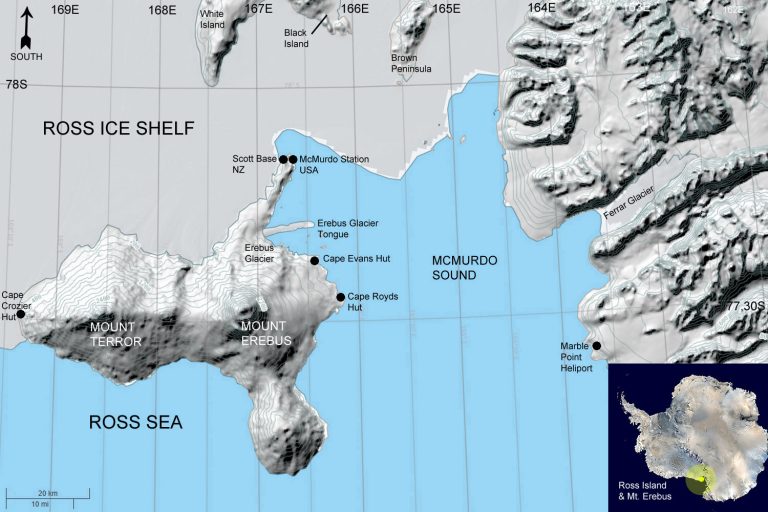

We then took a field trip to the Kiwi station, Scott Base, which is just a kilometer away. Scott Base sits on Ross Island, as well, but it’s directly next to the Ross Ice Shelf, which is a floating piece of ice connected to glaciers and land on the continent that reaches up to ~750 m thickness in some places. McMurdo, however, is on the other side of the peninsula where there is seasonal sea ice (just a few meters thick) that will melt in the late summer, allowing ships to port. When we get back to McMurdo in late January, the sea ice will have melted enough that penguins are likely to show up during their migration season!

On this field trip, we went to see the pressure ridges – large undulations in sea ice and the ice shelf that are caused by collisions between icebergs, ice shelves, and land. We were guided by Thor, who has spent 10+ seasons as a traverse lead driving large traverse vehicles out to the far reaches of the continent to support science. Thor took the group on a hiking trail on the sea ice, weaving in between lots of fat seals and their pups. We could see some amazing ice structures, the flat expanse of the Ross Ice Shelf, and many beautiful mountains in the horizon (such as Black and White Islands, labeled on the map above). We could also see Mount Erebus and Mount Terror, the southernmost active volcano, and an inactive volcano, respectively. It was a lovely hike despite it being incredibly windy.

After our hike, we stopped in Scott Base’s shop and bought some souveniers before shuttling back to McMurdo to get back to work. Ellen and I assembled some more of the EAGER radar while Dylen and Ilyse worked on testing the assembly of a box that will live at each of our field sites and hold almost all of the equipment.

We had dinner with Forest and Elliot before getting back to work for a bit before bed. Today is our last “free” day since the next week or so is peppered with many trainings to complete before heading out to the field.

Dec 1: Field safety

Happy December! Today is Monday so we started the first of our trainings with a science briefing and tour of the lab spaces, then pestered IT to pleaseeeeeee let us on the science wifi network. Ellen and I recruited Forest and Elliot to move some radar boxes from the cargo yard to the warehouse so we can spread out and assemble the ApRES.

Sidenote: Radar and ApRES

Quick science sidenote – what is an ApRES? What does it measure? Why are we using it?

The Autonomous Phase-Sensitive Radio Echo Sounder (ApRES) is a type of ice-penetrating radar system. A radar system has a transmitter that sends radio waves into the subsurface (in our case, ice) and a receiver that receives the wave after it reflects off of something in the subsurface and comes back to the receiver. Radio waves can bounce off of ice where its properties change (density, conductivity) and where there are material changes, like at ice/rock, ice/water, and ice/air interfaces. The returning wave has a power associated with it and we can convert its two-way travel time to depth so we know where the wave bounced in the subsurface and how much power was absorbed on the way there and back. This information lets us create radargrams, which are beautiful images of the subsurface!

The ApRES allows you to leave the instrument and program it to take measurements over time at programmed time intervals. Ellen and I will set up the ApRES in the field and set it to collect a measurement every day over the course of a year. As snow accumulates on top of the ApRES, the overburden pressure compresses the snow underneath the ApRES and the thickness of the snow beneath the ApRES decreases. Small changes in accumulation can be detected by the ApRES system since there is a small change in phase of the wave as the object that it bounces off of. The rate of the change in firn layers, combined with some other information about the snow, allows us to measure the rate of firn compaction over the course of the year! This is a new method, and we’re excited to compare the results to another method of measuring firn compaction that Dylen and Ilyse are doing.

After lunch, the team headed to a field safety course where we learned about recognizing cold injuries like frostbite, frostnip, chilblains, and hypothermia. We went over each item in the survival kits we will carry with us in the deep field, which include a tent, two sleeping bags, tent stakes for snow, rock, and ice, enough food for two people to last three days, a stove, fuel, foam pads, a few extra gloves and hats, and morale-boosting entertainment. We also got helicopter training and talked about risk management and hazard response.

Later that evening, Ellen and I spent some time chasing down other cargo and rewiring parts of the EAGER radar we wired incorrectly on Saturday. Dylen and Ilyse are testing their instruments in the lab – more about these later.

Around 8 pm, Dylen, Ilyse, Ellen, and I headed to the ObTube – a Super Mario-like observational tube stuck in the sea ice. The tube itself is ~20 ft long and was melted into the sea ice, held on the surface by some (hopefully) sturdy metal bars. One person can fit in the tube and they climb backwards down a ladder to another sketchy ladder until they’re not visible from the surface sitting in an underwater observatory. There are windows surrounding you deep in the ObTube and you can see and hear sea life! We saw thousands of fish, coral, and heard seals whistling to each other. It was amazing. We’re heading back tomorrow morning since the ObTube will be taken out this week because the sea ice will completely melt soon in the warm weather.

Dec 2: Core Trainings

Today, Dylen, Ilyse, Ellen, and I woke up early for a morning ObTube session! We heard more seals and saw what looked like a jellyfish. It was quite a bit colder and windier than yesterday’s heat so standing outside of the ObTube while someone was in there was particularly uncomfortable.

We headed to brekkie and settled in for a long (2.5 hour) Core Training. We got briefed by the many departments that make McMurdo work. Waste management taught us how to sort the many kinds of waste and recycling that get sent back on a ship to California. They refrigerate food waste (not compost but anything that has touched food including wrappers) because, if it was warm, it would show up rotten and moldy after the months-long trip back to California.

We also heard from the fire department (FD) who informed us about how to live in this desert environment. No candles, no daisy chaining power strips, and extinguish your cigarette butts before you throw them into the butt can! They talked about the water allotment for the FD here and how necessary the desalinization process is; if the FD doesn’t have their 50,000 gallon allotment of fresh water, they must start evacuating people.

We heard from the environmental team who talked about protected areas (like the Ross Sea and Antarctica in general), the Antarctic Treaty, and how far away from animals we must be (5-15 m). Our medical briefing included information about the facilities that the clinic has here (spoiler alert: there are not many).

After briefings, we all got to work on either assembling radar systems or debugging strain gauges. Zoe and I picked up our field communication devices which include 12 hand radios and a larger radio station for communication between team members in the field, three satellite phones (two for comm with McMurdo and one for morale), and a high-frequency radio for communication with McMurdo. We all collaborated on the science talk we’ll give tomorrow where Zoe will introduce our project and the rest of us early-career researchers will talk about specific details about our equipment and methodology.

Next was dinner and an outdoor safety training. Now that we’ve completed this training, we can explore the trail network outside town!

Dec 3: EarthScope

I woke up early to get some “me” time and read a book during breakfast before finishing my slides for tonight’s presentation. Today was cold and windy again, with some very, very light snowfall. My hair froze within one wind gust while walking between buildings.

The team had our morning meeting then we headed to various meetings and trainings. First, GPS training, where we learned how to use portable GPS devices that we’ll use in the field. We will use the devices to navigate to waypoints, including the coordinates of the four field sites we are going to set up. GPS training ended with a little scavenger hunt practice where we used the devices to navigate on a pre-set route and find our instructor.

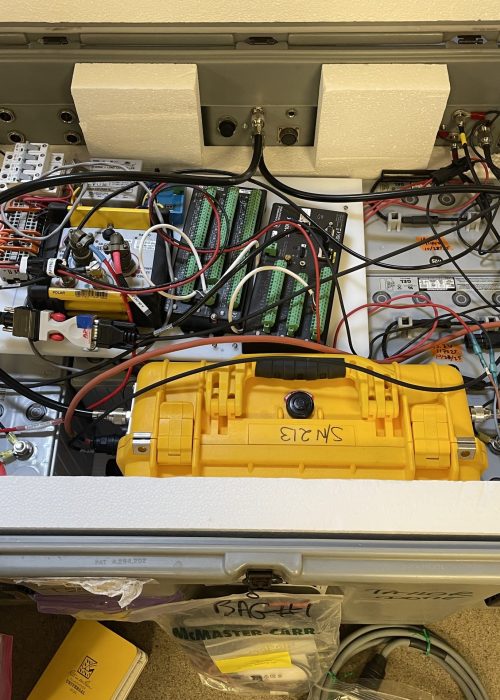

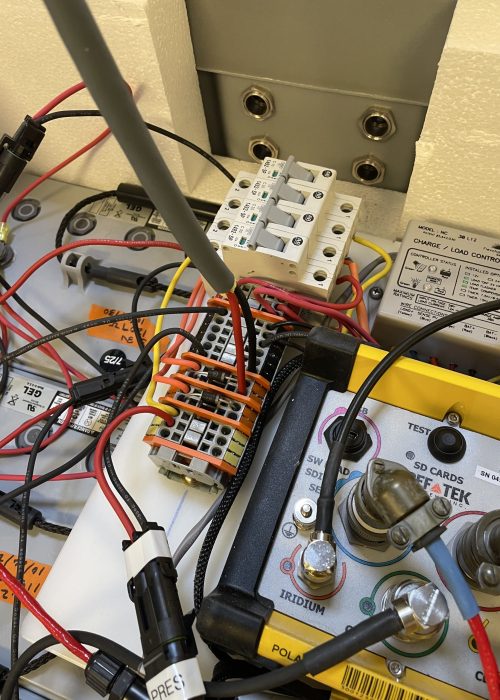

Next, we headed to a meeting with EarthScope engineers. EarthScope made four custom Pelican-Hardigg cases for us to fit our components in at each site, and four more battery cases to hold a total of fifteen 100 amp-hour batteries between the two cases at each site. Nick, an EarthScope engineer, taught us how to connect our many instruments to the custom cases and how to wire the fifteen batteries in parallel so the fifteen batteries act as one enormous single battery.

We’ll be deploying strain gauges to measure firn compaction, an ApRES to also measure firn compaction, an anemometer to measure wind speed, a thermistor to measure temperature in a borehole, and a GNSS to calibrate time (and location, I guess, in case the box drifts). We’ll collect data on SD cards that someone will need to collect in a year, and we’ll be transmitting some data using Iridium’s satellite transmission services. We’ll also set up a solar panel to charge the batteries during the summer.

Each case requires quite a bit of setup and coordination for each instrument and the fifteen batteries since they need to be protected by the Hardigg cases buried in the snow for two years. It’s a tight squeeze! The batteries are the size of a cinderblock and weigh ~75 lb each, making it a non-trivial task to carry fifteen from camp to four field sites (up to ~12 km away) via Ski-Doo (snowmobile). We’ll be incredibly strong at the end of the season from lifting batteries all the time.

After dinner, we gave a science talk about our project! It was such a whirlwind, I forgot to get a single picture… Anyway, we split the talk into pieces where the early career researchers talked about parts of the project and Zoe introduced the motivation and some historical work at Taylor Dome. We got lots of great questions and people loved our stickers! Ellen designed a Taylor Swift Eras Tour-inspired sticker with a firn core posing as Taylor.

Dec 4: Zoomin

This morning, Ellen and I had a call with John and Knut, two faculty members who designed one of the fancy new radar systems that we’ll be using. The EAGAR radar has the ability to image the subsurface from multiple angles, allowing us to see grain-scale structures and patterns. This is particularly useful for understanding firn microstructure, which is a key component that is missing from current firn models.

The meeting itself was difficult to conduct – between the slow wifi here and the mess of cords leading to the Zoom laptop, it’s difficult to describe which wire/button/plug/screw one is referring to when we have hundreds of these components all over the radar system. Ellen and I made some progress, however, and we’re almost done assembling the EAGAR itself so we can get straight to work taking measurements in the field.

Later in the afternoon, we put together our sleep kits. They consisted of an extreme cold-rated (up to -40º) sleeping bag, a fleece sleeping bag liner, a foam pad and an air-filled sleeping pad to sleep on, a cot also to sleep on, a camping pillow, Nalgene bottles to store our pee (more about this in a minute), a couple of thermoses, and a Nalgene coozie (for the Nalgene we will store water in!). It’s also standard practice to boil water, pour it in a Nalgene, and put it in your sleeping bag to warm it up before you sleep. Tomorrow, we’ll do the Deep Field Shakedown: we’ll test out our ECW gear and sleeping setup, practice setting up our tents, and sleep out in the field to make sure we have the right gear and to test before the real thing.

Sidenote: hygiene in the field

Per the Antarctic Treaty, Antarctica is a protected place, and we must treat it with respect, which includes taking care of our waste. Besides shipping recycling, metals, hazardous waste, and landfill garbage off of the continent, USAP has policies about human waste. No one is permitted to deposit human waste on the continent, unless you are in an accumulation zone (where there is enough snow that the waste can be covered relatively quickly). There is enough accumulation across Taylor Dome for us to not have to worry about collecting our waste there.

In places where you must carry out all of your waste, USAP supplies pee bottles and plastic bags for going number two. The pee bottles are normal Nalgene water bottles with “PEE” written all over them. They’re useful for going on hikes or longer adventures in places where (1) you can’t leave your waste on the continent and (2) there is no bathroom. At Taylor Dome, they’ll also be useful for peeing when we’re in our personal tents. Imagine waking up in the middle of the night and you have to pee… Would you want to put on five different layers, wrestle with your boots, and step outside of your (relatively) warm tent into the bright sunlight to trudge over to the bathroom tent to do your business? I prefer a water bottle, instead. Plus, a fresh (and tightly sealed) pee bottle makes for a great sleeping bag warmer…

Dylen, Ilyse, Ellen, and I collaborated on a standard operating procedure for setting up the EarthScope boxes. There are so many connections and components that go into and out of the box that we needed to put our heads together to make sure we were all on the same page. Whoever comes back in a year (in case it’s not any of us) to dig up the EarthScope cases and collect the data will need to know how the case works.

We ended the day by packing for tomorrow’s Deep Field Shakedown, woohoo!

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed are solely my own and do not express the views or opinions of the National Science Foundation, the United States Antarctic Program, or the University of Washington. This blog is for entertainment purposes only.

Fantastic updates. The descriptions, the humor and the pictures make me feel like I’m part of the experience. Thanks for allowing me to live vicariously!

Claire this is amazing!! Thank you for sharing and I am still thinking about the pee bottles!! What an adventure!! Can’t wait till the next post!! Keep making memories and sending pictures!! The seals and ice shelves were gorgeous!!

Quite the adventure! I look forward to reading about your future endeavors. Stay warm…ish!!

My head is spinning seeing all the machines and wires! Oh Claire, such an amazing adventure!! You know, I would be so tempted to pet those adorable seals.

Love the seal pictures🦭

Love the blog! Excellent sidebars and photos. Great coverage of the science and the life of an Antarctic field researcher. Thanks for sharing!